@import url(https://www.blogger.com/static/v1/v-css/navbar/3334278262-classic.css);

div.b-mobile {display:none;}

Below is a review of the Victoria and Albert's current exhibition, Postmodernism: Style and Subversion 1970-1990, which I spoke about briefly yesterday. This review was written for the Russian edition of the academic journal, Fashion Theory, but I thought I would post this here now as I'm sure most of you are not well versed in Russian.

In its bid to be seen as the “world’s greatest museum of art and design,” the Victoria and Albert Museum often takes on the role of the ‘definer’ of design history, choosing to mount exhibitions that set perceptions of genres and movements. Just as their exhibition on Art Nouveau in the early 1960s resuscitated and marked the boundaries of that movement, so too does their current exhibition, Postmodernism: Style and Subversion 1970-1990, attempt to do so for one of the more controversial periods in design history. Beloved by some and hated by many, postmodernism affected every aspect of design and lifestyle in the West and is still the predominant influence today. By setting the period of 1970 to 1990, the curators are to some degree defining what could be called ‘High Postmodernism,’ which they say is “an unstable mix of the theatrical and theoretical, the movement defies definition.”

Alessandro Mendini, destruction of Lassù chair, 1974. © Atelier Mendini/ Image courtesy CSAC-Universita' di Parma

Lacking such clear attributes as modernism and other movements before it, the V & A tries to define postmodernism in opposition to its antecedents — as nihilistic and colourful compared to modernism’s utopian clarity. The design of the exhibition establishes this difference from the beginning, with the wall text printed on an orange plexi lightbox and a wallpaper of little black squiggles on white covering the walls of the first room. The first object, Alessandro Mendini’s Destruction of the Monumento da Casa (Household Monument) (1974), is an enlarged photograph of his ritualistic burning of a Modernist chair — literally destroying the past — and is positioned opposite a wall-size blow-up of a photo of the dynamiting of the Pruitt-Igoe housing project in St. Louis in 1972, which was considered by Charles Jencks, the pre-eminent authority on postmodernism, as the death of modernism. This first room focuses on Italian artists and designers who at the beginning of the 1970s looked to American pop culture for inspiration, which would become one of the most important components of postmodern design.

The replica of Charles Jenck’s Cape Cod Garagia Rotunda studio (1976-7) in the background.

Architecture was the first art form where postmodernism was developed and analysed on a broad scale, and the next few rooms cover the inspiration (the Las Vegas strip, historicism) and the outcomes, including almost life-size scale replicas of Charles Jenck’s Cape Cod Garagia Rotunda studio (1976-7) and Hans Hollein’s façade from the 1980 Venice Biennale.

Hans Hollein’s façade, with columns representing the history of architecture, from the 1980 Venice Biennale.

Theory and philosophy were critical to the development of postmodernism, and are an integral component of it, yet this exhibition, likely for the benefit of the general public, sidesteps almost all mention of it. Postmodernism is viewed in this manner as a purely aesthetic movement, unattached to broader socio-cultural events and philosophical debates. Claude Lévi-Strauss’ definition of bricoleur is briefly explained in regards to bricolage, the cut ‘n’ paste technique that combines diverse references, before attention is turned to look at the dystopian worldview associated with some strains of postmodernism. A reaction to the utopia of modernism, this theme is most clearly seen in Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982), which is shown on a large screen.

A Vivienne Westwood outfit from Punkature (s/s 1983) with a skirt printed with images from Blade Runner.

Below the film are the first two fashion pieces in the exhibition — a Vivienne Westwood rag-bag ensemble from Punkature (S/S 1983) and an early Rei Kawakubo for Commes des Garcons jumper and skirt (1982) that is described as ‘post-holocaust fashion.’

Memphis Group designs.

From the apocalypse to the bright, colourful world of the Memphis Group, the difference between these two rooms could not be starker. Filled with the geometric, multicolored furniture and housewares by the group, the following room visually echoes their aim to occupy a “a state of waste, of disciplinary, dimensional and conceptual indifference.” Unlike anything that had been produced before, the work of Memphis (established in 1981) and their predecessor Alchymia (1978) is the joyful representation of postmodernism — colors and references combined in an almost absurd way. The sole garment in this room is a remarkable dress by Memphis associate, Cinzia Ruggeri, in homage to Lévi-Strauss with a ziggurat shaped asymmetric skirt and collar (A/W 1983-84), carefully displayed on a mannequin with matching asymmetric hair and makeup.

The 'Strike a Pose' section.

The influence of postmodernism on dress is more closely looked at in the next section, Strike a Pose, a room of multi-level scaffolding and platforms, reminiscent of Blade Runner— including two costumes from the film. Analysing the close connection between performers, their outfits and postmodernism, this room displays an assortment of costumes from musicians, singers and dancers, alongside videos and photographs of their performances. Through their deconstruction and reconstruction of their identities through costume, performers such as Klaus Nomi and David Byrne of the Talking Heads created innovative visual languages that complemented their avant-garde music, while Jean-Paul Goude’s creation of Grace Jones’ persona as a savage, androgynous Amazon — through carefully constructed photographic imagery and videos — can be seen as the ultimate construction of a postmodern identity. His Constructivist maternity dress for her (made in conjunction with the illustrator, Antonio Lopez, in 1979), a sculptural form of intersecting geometric planes of brightly coloured felt and cardboard, is mounted on a mannequin far above the visitors heads, promoting the idea that she is the ‘high priestess of postmodernism,’ as mentioned on the label.

Maternity dress for Grace Jones, by Jean-Paul Goude and Antonio Lopez (1979). © Jean-Paul Goude

Equally interesting, but less well known, are pieces like Leigh Bowery’s costume designs for Michael Clark’s dance performance, Because We Must (1987, filmed in 1989 by Charles Atlas), which combine 17th century inspired crewel embroidery with pink sequins and gimp-like masks. Also on view are a costume from Ōno Kazuo, the Japanese avant-garde dancer, and several from the Armitage Ballet, designed by well-known artists including David Salle and Jeff Koons. Large screens mounted at different levels on the scaffolding alternate clips from music videos by Nomi, Jones and Talking Heads; almost bombarding the senses with the frenetic nature of postmodernism.

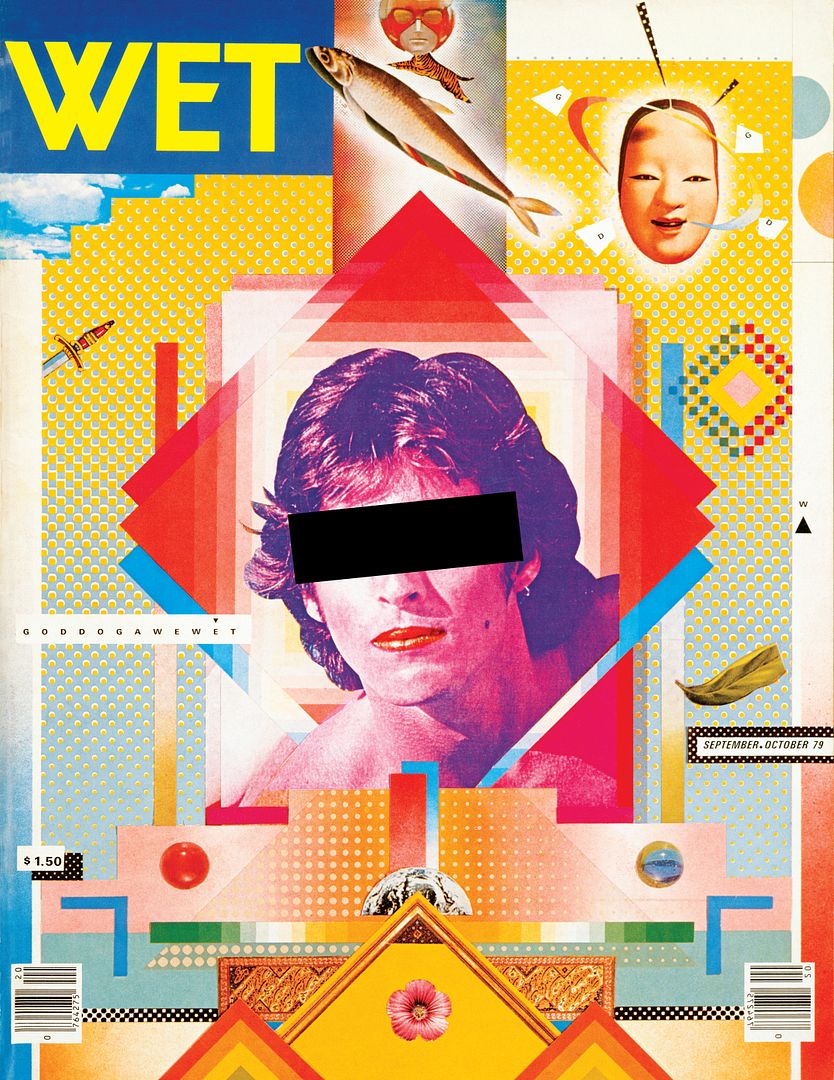

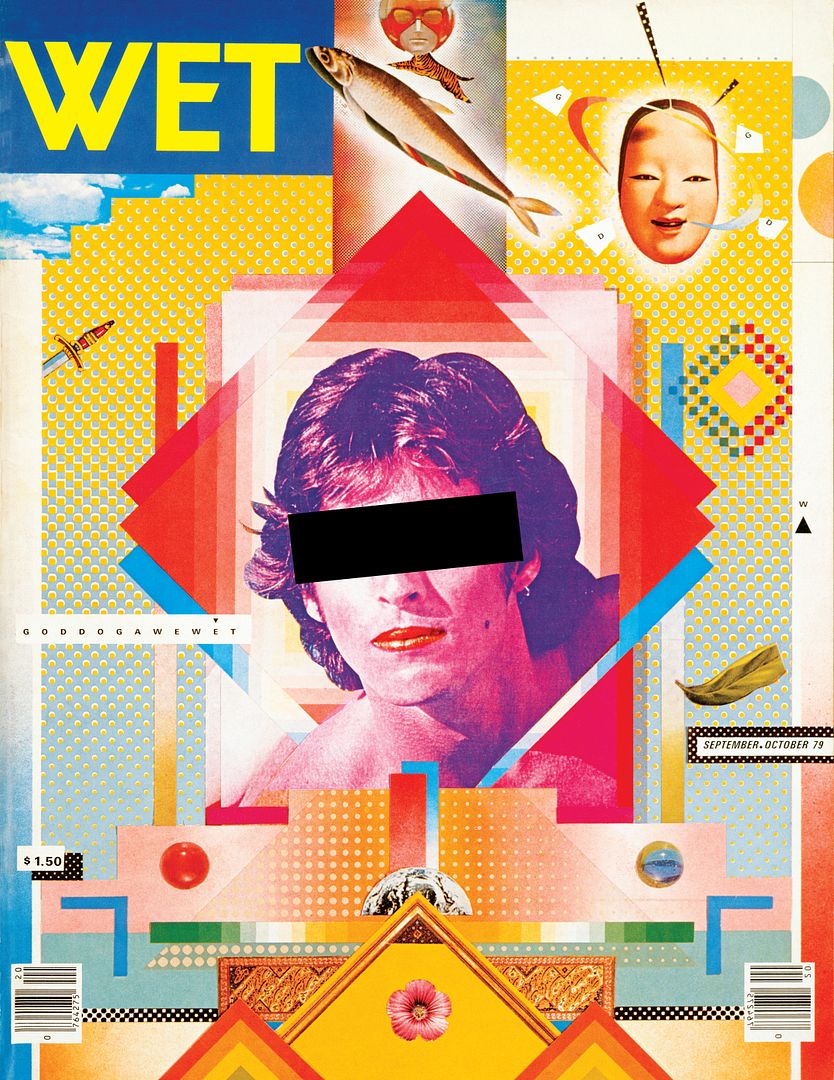

Wet: The Magazine of Gourmet Bathing no.20. Design by April Greiman in collaboration with Jayme Odgers, Sept/Nov 1979 religion issue edited by Leonard Koren.

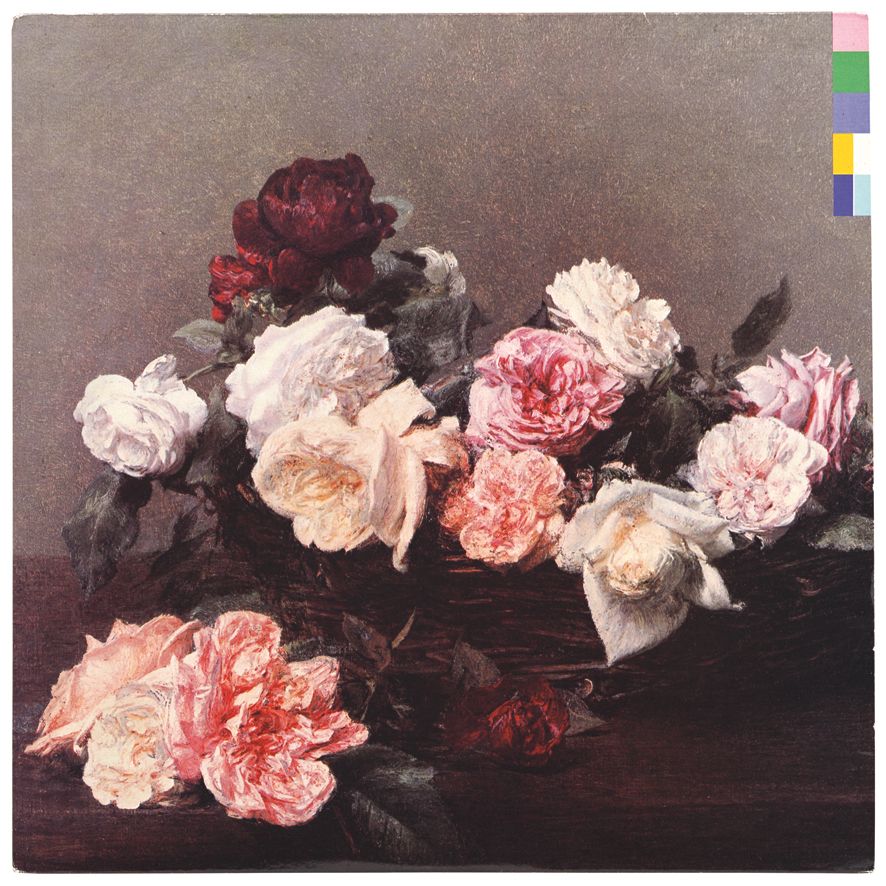

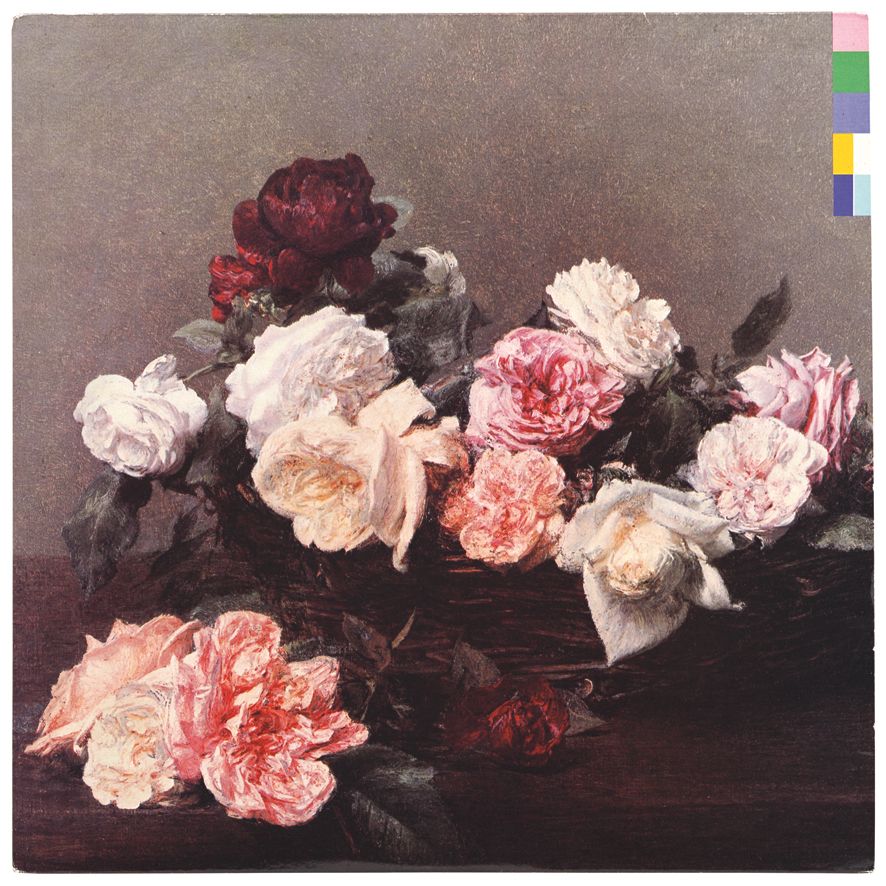

Power, Corruption & Lies album cover for New Order, by Peter Saville (1983) © Peter Saville.

Magazines and the graphic arts were an ideal vehicle for postmodernism’s use of fragmentation and quotation, and in the 1980s The Face and i-D helped to transmit these design ideas to more people. Album covers, particularly for post-punk bands such as Joy Division and New Order, were also representative of this particularly postmodern phenomenon, where there was no difference between art and commerce. The use of postmodernism as a means to sell (posters, etc) leads into the last major section of the exhibition, simply titled ‘Money,’ where postmodernism becomes the commodity in itself. Karl Lagerfeld’s sequin reworking of a classic Chanel jacket (1991) is positioned directly after Warhol’s Dollar Sign print (1987), and is followed by sketches and models of some of the more over-the-top buildings constructed in the boom years of the late 1980s. As postmodern designers began to partner with more mass-market producers — selling teapots and other household goods to all price points — they became complicit in their success and their demise. The amalgamation of references were viewed as pastiche and became antiquated as soon as the markets started to fall, with anything classic and traditional seen as a safer bet — “postmodernism collapsed under the weigh of its own success” and became so mainstream and omnipresent that a backlash was inevitable.

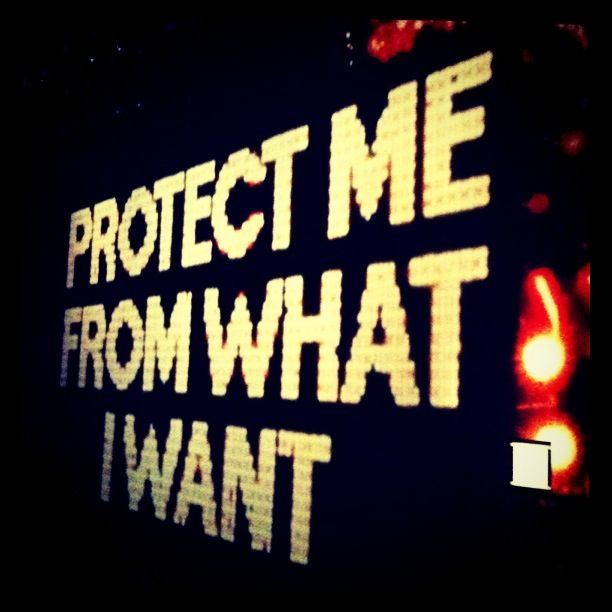

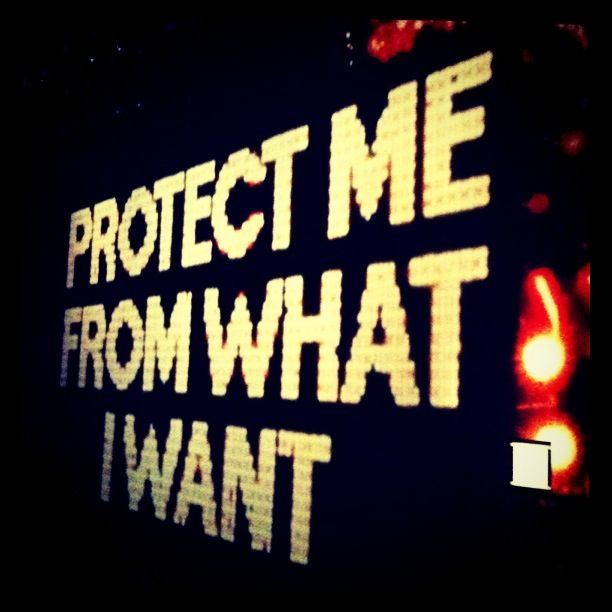

Jenny Holzer's billboard in Times Square, 1982.

Finishing up with a few late 1980s artistic reactions to the movement and a small room screening New Order’s video for Bizarre Love Triangle (1986), this exhibition covers most aspects of postmodern design and will likely help many visitors understand it aesthetically. Focusing primarily on the decorative arts and architecture, fashion is seen here almost solely in the context of performance, yet postmodernism’s influence on fashion, and dress in general, was monumental — by throwing out the rules, postmodernism shifted our ideas on what, when and why we dress the way we do and allowed for the mass proliferation of different contemporaneous styles that we have today. From a fashion perspective, this exhibition would benefit from both more high-end designer pieces as well as cheaper mass-market garments that might aid the museum visitors in relating to postmodernism on a more personal level, by displaying something similar to what they might have worn in the 1980s while also explaining where it came from and the design aesthetics that inspired its creation. The final text of the exhibition announces, “we are all postmodern now”; a statement that is difficult to disagree with in light of the patchworking of historical and cultural themes on the runway and in stores, and a statement whose importance will hopefully be understood more clearly following this retrospective.

Text by Laura McLaws Helms, 2011. Images 2, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9 are from the VAM image library, while 3, 4 and 10 were taken by me on my iPhone.

Labels: 1970s, 1980s, design, exhibition reviews, exhibitions, memphis, postmodernism, russian fashion theory, victoria and albert museum